Kappabashi is Japan’s kitchen wonderland, with restauranteurs and amateurs alike flocking to the main street every day to browse the amazing tools on offer. And no object is more sought-after than Japanese knives. But with so many options, where should you start?

Where to go: The big three for Kappabashi knife shopping

There are dozens of knife shops on the main road and surrounding side-streets—so it’s well worth setting aside a day to wander around and get a feel for what each shop has to offer. These three shops are the most well-known, and are very used to dealing with foreign customers. Be sure to bring your passport if you want to buy your knife tax-free.

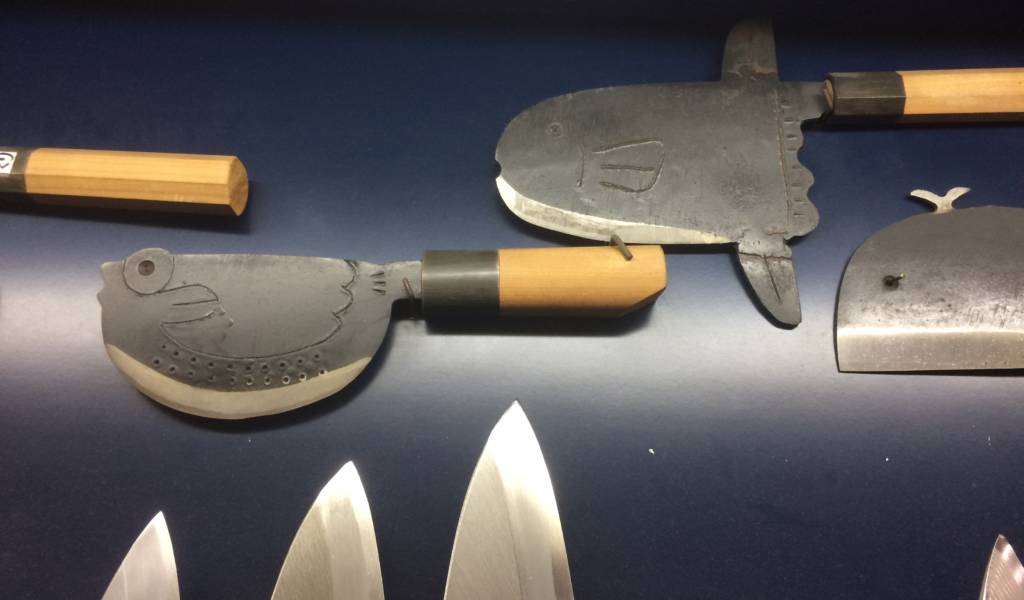

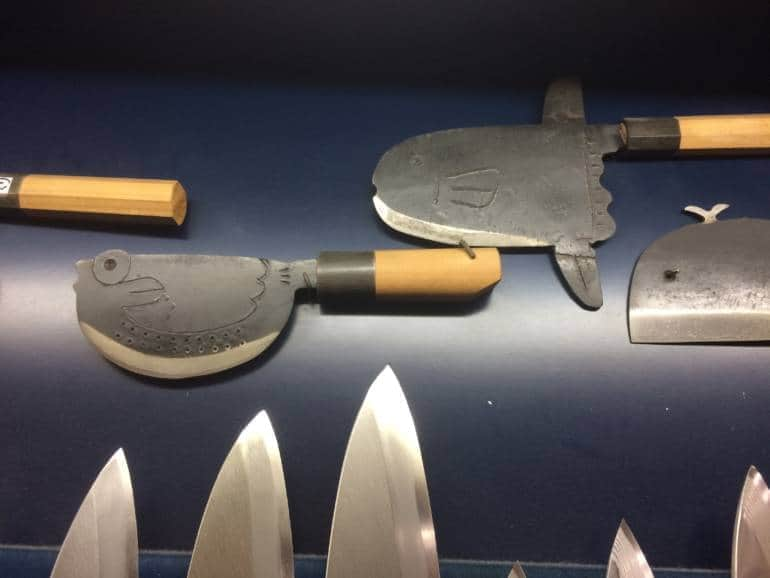

Tsubaya

Tsubaya is a narrow store absolutely crammed with knives of all kinds. That includes a wide variety of specialty and even novelty knives. The stickering system here makes it easy to see what kind of steel you’re looking at.

Any knife with a yellow sticker is carbon steel, while green refers to stainless. Tsubaya appears to have the widest selection available, and allows you to handle most knives without calling staff to open a cabinet. That makes this a great starting point to try out each knife and get a feel for the weight, price and shapes that work for you.

Kamata

This immaculately presented store is a must-visit while in the area. The third-generation owner, Seiichi Kamata is renowned as a master sharpener, and the store personally sees to making sure each knife has a perfect edge before it’s sold. You can also sign up for a knife sharpening class here. It costs ¥5,000, but comes with a professional whetstone worth ¥5,400, and a certificate card saying you’ve passed. What’s more, you’ll also get a 10% in-store discount with the card. If you aren’t able to get a spot on the notoriously difficult-to-book class, you can take your knives back to Kamata to be sharpened by the master from around ¥1,000. Find out more about the class (Japanese only)

Kamaasa

While Kamaasa is a general cookware store, the first floor deals almost exclusively with quality knives. The knives are neatly sorted by category, and there are stations at which knowledgeable staff members will happily talk you through the benefits and drawbacks of each knife. This store also had the best selection of whetstones of the big three, so if you’re interested in learning to sharpen, it’s a great place to start.

Types of metal

Broadly speaking, the biggest decision you’ll have to make is between stainless steel and carbon steel.

Stainless steel

Most everyday knives are made with stainless steel, where steel is mixed with chromium, (among other metals), which makes the steel less reactive.

The main benefit here is that it’s super resistant to rust. You could leave a stainless-steel knife out in the rain for a month, clean if off and you’d be good to go. The downside is that it doesn’t hold an edge so well—so it won’t get as sharp and you’ll need to sharpen it more often to keep it in tip-top condition.

Carbon steel

Carbon steel has a higher proportion of (you guessed it) carbon. This makes it super hard—so you’ll get a keener edge that stays sharp for longer. The downside is that it tarnishes super easily—any traces of water on the knife will quickly form rust spots. If not treated, these can spread and weaken the metal.

However well you take care of your knife, it’s likely to develop a patina—a thin coating of discoloration. There are apparently ways to speed up or influence the appearance of this patina, but either way it’s probably going to happen. Unlike rust, a patina is usually considered a good thing, as it acts as a protective layer. That said, it’s worth knowing that if you’re buying a knife for its appearance alone, a carbon steel knife will very likely change dramatically with use.

Another word of warning, carbon steel is also more brittle than its stainless counterpart, so it’s prone to chipping, especially on the tip. If you’re the sort of person that throws caution to the wind and uses kitchen knives to pry open cans, crack bones, tighten screws or break apart frozen foods, carbon steel is not for you.

Choosing a blade shape

Your next big decision will be on what kind of knife you want. The majority of buyers are looking for a versatile chef’s knife—so that’s what I’ll cover here.

French chef’s knives

This is the classic Western chef’s knife—with a broad heel (the side of the blade closest to your hand) tapering to a sharp point. Generally speaking there’s a slight curve to the blade. As a result, these knives are perfect for rolling chop techniques, or for using the tip as a cutting guide.

Santoku chef’s knives

Santoku knives are based on more traditional Japanese knives, and feature a broad blade and blunt tip. Apparently, the word santoku alludes to the “three virtues” of the knife. I’ve seen that explained as the knife being good for fish, meat and vegetables. That said, I’ve also read that it refers to chopping, dicing and mincing. Either way, santoku knives are super versatile, and can be used for the majority of tasks. There’s a lot of variation in the curvature of the blade—some have a flat blade, which makes a rolling motion more difficult, while others have a more forgiving curve.

Double or single bevel

Most Western-style knives have a double bevel—which means the blade is sharpened on both side to form a v-shape. These days the same goes for most Japanese home knives.

A single bevel blade is only angled on one side—making it more of a doorwedge shape. Unless you’re a top-level sushi chef (thanks for reading!) or you need to execute some fancy knifework, you should probably avoid spending big bucks on a single-bevel knife. They’re tricky to handle—especially if you don’t know what you’re doing. On the other hand, for practiced users, they’re capable of making thin slices that would be practically impossible using a similar-sized double-sided knife. Single bevel knives are usually right-handed unless otherwise stated. Left-handed knives can be pain to sharpen even for professionals—consider yourself warned!

Tang and handle

The metal part of the knife that’s not the blade? That’s the tang—it goes into the handle and provides weight and support.

Full tang

Most decent Western-style knives are full tang, which means the metal goes all the way through the handle. They’re usually pinned in with rivets for stability. It’s usually easy to know if your knife is full tang, since you can see the metal stripe following the spine of the knife, sandwiched by the handle. A full tang knife is as stable as it gets—the handle is unlikely to break off. Because of the added weight, it also gives the knife some balance and heft, which some users prefer.

Partial tang

Japanese knives traditionally have a shorter tang, which stops around halfway down the handle. The tang is held in by a mix of pressure and adhesives—making for a less durable bond. There’s a good chance over heavy usage you’ll need to get a Japanese-style handle replaced or repaired. Fortunately, that’s easily done (as long as you’re in Japan). A partial tang can lead to a much lighter knife, with more weighting on the blade end. This can be especially useful for chunkier single-bevelled Deba knives and long yanagi knives for cutting sashimi.

Handle shape and material

The most common wooden handles are made from magnolia. Because they’re cheaper and easier to replace over time, many chefs opt for this even for expensive blades. There are plenty of other options though, including durable resins, and more expensive woods like ebony.

Cheaper unvarnished wooden handles can warp with water, and will discolor from your hands (and whatever is on them) over time. Luckily, there are plenty of waxes and varnishes out there to use if that bothers you. Otherwise, you can let nature take its course and just replace the handle occasionally.

Handle shape is very much down to personal preference. While I prefer Western-style grips, which are moulded to the hand, many prefer a Japanese style handle. These generally come in more regular ovoid and octagonal shapes.

Patterning

Named after the now-lost forging techniques of Damascus, the best-known pattern, Damascus steel, is formed by layering thin sheets of steel up to hundreds of times to form an impressive wave effect over the surface of the blade. Other effects include pock marks, mirror polishing and engraving patterns, such as cherry blossoms, onto knives. Many of these effects are purely aesthetic. However, some are formed when layers of softer steel are used to coat a central, harder steel. This technique is often used strengthen the knife, providing rust and shock resistance along the non-cutting surfaces.

Prices

There are so many variables that it’s hard to say how much a good knife costs in Kappabashi. Depending on the size, metal, shape, materials and artistry involved, you might end up paying anywhere from ¥5,000 (for a small paring knife) to ¥500,000. Ultimately, it’s up to you decide on your budget and pick a knife that best suits your specific tastes and tasks.

Cheapo tip: In the past, we’ve received small discounts (5–10%) when buying knives in cash (versus credit card).